Ahmose Tomb Excavation

The ASP kicked off in 2018 with a plan to relocate the tomb of Ahmose.

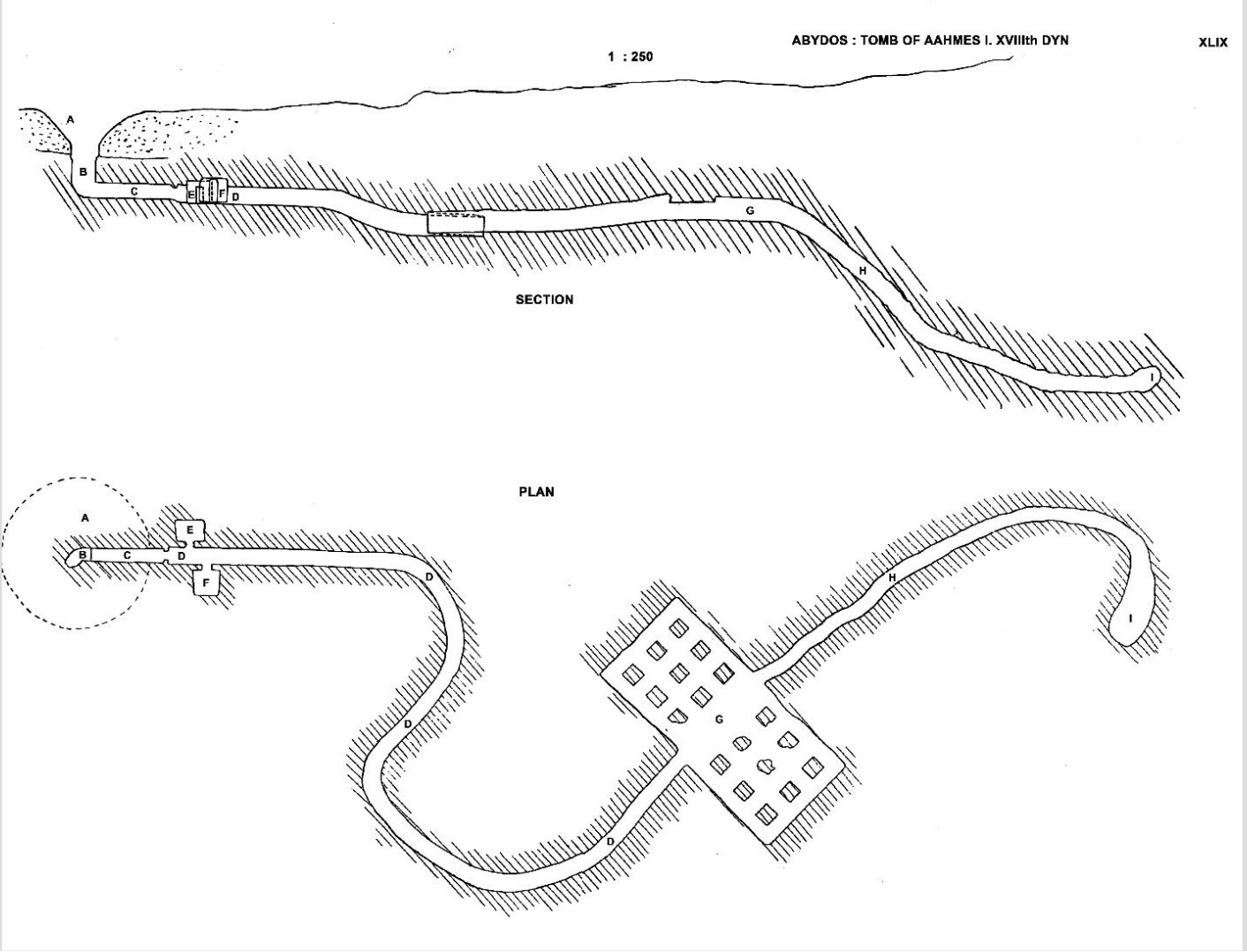

The tomb was first discovered by Canadian archaeologist Charles Currelly, working for the Egypt Exploration Society under the direction of Flinders Petrie in 1904. His team cleared the underground, curving tomb chamber and created a basic plan and elevation, published in Abydos, Part III, by the Egypt Exploration Fund.

The tomb chamber is cut into the natural rock lying beneath the desert sand. With no marking left behind and somewhat imprecise documentation common in early 20th century archaeology, the exact location of the monument remained unclear. Using additional recent survey data and a lot of patience, the 2018 team began searching in the low desert.

After digging through many meters of uncooperative loose sand, the team finally came down to a cut at the middle of the tomb near the collapsed pillared hall. They cleared the upper part of the chamber and areas of the pillared hall for documentation. Unfortunately, the fragile state of the remaining tomb extending to the burial chamber made it impossible to fully clear and document.

The identification of this monument as the true tomb of Ahmose is debated in the field of Egyptology. Ahmose’s royal family had an ancestral cemetery in Luxor reaching back several generations and then continuing on after his reign for the rest of the New Kingdom. In addition, a mummy identified as Ahmose was recovered in Luxor in the famous Deir el-Bahri cache. Yet the design of the monument follows long-standing royal traditions of burial, in particular the nearby rock-cut tomb of Senwosret III. The other monuments in his complex, especially Ahmose’s pyramid, and the association of Abydos with Osiris, the god of the dead, suggest Ahmose may have intended this for his burial, whether it in fact occurred here or in Luxor.

The fragility of the tomb and its location under the low desert creates a complicated context for future work, but it remains on the list of priorities for the ASP. We hope to return to this project in the future.

View of the curving walls inside the cleared tomb chamber of Ahmose

VIew over south Abydos from the western cliffs, with the pit over Ahmose’s rediscovered tomb at the upper right.

Plan and elevation of the tomb after Currelly, from Abydos, Part III, pl. LXIX

Reis Ashraf Zeydan inside the partially cleared interior of the tomb.

Excavations Near the Ahmose pyramid: the Ahmose cemetery and Administrative buildings

Starting in 2022, the ASP undertook a new excavation project in the area local north (true west) of the Ahmose Pyramid. It appeared no previous systematic excavation had taken place in this area, other than a brief survey undertaken by the MoTA in the 60s, a test trench by David O’Connor in the same era, and some surface collections in later years.

The area had long been attributed as the site of the Ahmose Pyramid Town, based upon, primarily, an early and limited understanding of the town of Wah-Sut, discovered by Currelly and the EES in the early 20th century. Because similar pyramid-adjacent settlements were known at other sites, and because Ahmose’s pyramid was the only one known in Abydos, when Currelly and team discovered Wah-Sut, they presumed it followed a similar pattern.

In the late 20th century, Josef Wegner at the University of Pennsylvania returned to Wah-Sut, and through his extensive and careful excavations, determined it was in fact an initially Middle Kingdom settlement that was associated with the royal building project of Senwosret III at Abydos. His detailed work showed Currelly’s mis-identification, yet the reference to the Ahmose town remained, just shifted ever southward toward the pyramid.

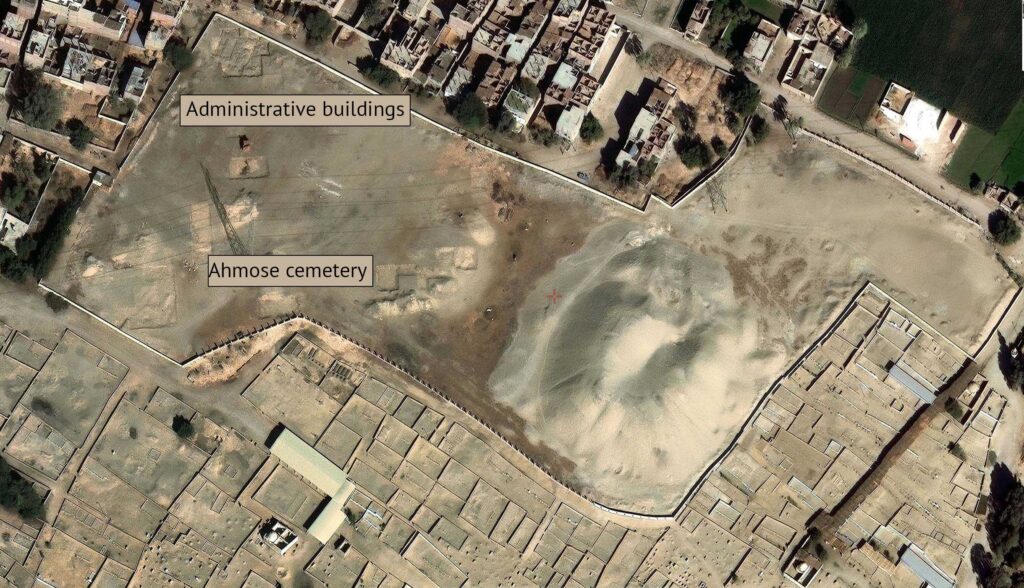

The ASP excavation began by setting squares across the open area near the pyramid in an effort to get an initial understanding of the entire space. This work revealed that the space had in fact been used for multiple purposes in the ancient context, with large, administrative style buildings along the local east, and burials across the local west, including a previously unknown cemetery, referred to now as the Ahmose Cemetery.

The Ahmose Cemetery extends from the edge of the depression alongside the pyramid to the end of the antiquities land concession at the local north end. The ASP has so far excavated approximately 40 burials. Surprisingly, the burials closest to the pyramid were the most simple, mainly wooden coffins set directly into the sand, with some others in simple pits, all with at most modest collections of ceramic offerings.

The core of the cemetery with more monumental burials including tomb shafts, burial chambers, and surface architecture, is set at the furthest north from the pyramid. Three large shafts with multiple burial chambers are surrounded by an array of more simple pits sunk into the rock. Remains of mud brick surface architecture including U-shaped chapels and small enclosure walls indicate the cemetery’s visible presence in the ancient landscape. The finds here suggested the higher status of the buried, with painted wooden coffins, finely painted ceramics, and the remains of a limestone stela in one of the chapels.

One of the brick walls blocking a burial chamber included several mud bricks stamped with cartouches enclosing the throne name of Ahmose, “Nebpehtyre, beloved of Osiris”. The ceramic remains also date the cemetery to the earliest part of the 18th Dynasty.

This part of the cemetery was excavated by Emily Smith-Sangster, and her analysis of the material will be the subject of an upcoming monograph. The cemetery clearly extends to the north and west; further excavation will hopefully help enhance our knowledge of this new and important discovery.

To the local east of the cemetery, the ASP excavated remains of several very large scale mud brick buildings. While certainly used by the living and filled with remains of domestic types of pottery, the structures do not suggest a settlement. Instead the closer parallels are several large buildings at the site of Deir el-Ballas to the south, the site built by Ahmose’s father. Further excavation of these structures in future seasons will help to illuminate their purpose.

Dr. Smith-Sangster published a short review of this material in Expedition Magazine, which can be accessed here: https://www.penn.museum/sites/expedition/an-elite-necropolis-in-south-abydos/

Overview of administrative buildings area

View of the areas excavated local west of the Ahmose Pyramid

Overview of the core Ahmose Cemetery

Detail of mud brick from burial chamber blocking wall with Ahmose cartouche

Painted wood anthropoid coffin face

Excavations at Tetisheri

The Tetisheri mud brick pyramid had been excavated previously, first by the EES under Currelly in the early 20th century, and then by the University of Chicago under Stephen Harvey in the early 2000s. The ASP returned to this monument with a primary goal of conservation, but the work necessitated excavation as well.

The ASP began by removing backfill remains left from previous work. Once complete, work proceeded with excavation to the foundations of all of the walls, in order to clarify the structure of the building and provide data for its conservation.

The ASP discovered several pits that had been dug prior to the building of the pyramid, most likely for burials, but found no remains inside. It is likely, and even unsurprising, that the area had been used for perhaps modest burials during an earlier era. Future excavation in the area may help to illuminate this.

The excavations determined the pyramid had a 24m x 24m footprint, and the slope of the sides was 2:1, meaning the original monument stood 24 meters high. The internal casemate structure allowed the exterior slope to be achieved by corbeled vaulting around the entire monument, which is reflected in the conservation work.

The excavations also discovered that the main internal corridor had been originally paved with mud bricks, and the walls of the corridor seem to have been plastered and at least partly white-washed.

As earlier work had already shown, the pyramid had collapsed in several phases in the ancient context, and it was reused in later phases both for human burials and animal burials, especially dogs around the local southwest corner.

The excavations relocated the brick wall enclosing the pyramid complex. Future work will continue in these areas, leading to conservation of this wall as well. In addition, further work in the interior space of the pyramid will help us assess the ancient ritual spaces and complete conservation there as well.

3D model overview of the pyramid after excavation

View of the pyramid before ASP work

During ASP work showing ancient collapse and ongoing interior conservation

View of the internal corridor with remains of mud brick and paved floor, as well as debris from earlier work